Water turbine

A water turbine is a rotary engine that takes energy from moving water.

Water turbines were developed in the 19th century and were widely used for industrial power prior to electrical grids. Now they are mostly used for electric power generation. They harness a clean and renewable energy source.

Contents |

History

Water wheels have been used for thousands of years for industrial power. Their main shortcoming is size, which limits the flow rate and head that can be harnessed. The migration from water wheels to modern turbines took about one hundred years. Development occurred during the Industrial revolution, using scientific principles and methods. They also made extensive use of new materials and manufacturing methods developed at the time.

Swirl

The word turbine was introduced by the French engineer Claude Bourdin in the early 19th century and is derived from the Latin word for "whirling" or a "vortex". The main difference between early water turbines and water wheels is a swirl component of the water which passes energy to a spinning rotor. This additional component of motion allowed the turbine to be smaller than a water wheel of the same power. They could process more water by spinning faster and could harness much greater heads. (Later, impulse turbines were developed which didn't use swirl).

Time line

The earliest known water turbines date to the Roman Empire. Two helix-turbine mill sites of almost identical design were found at Chemtou and Testour, modern-day Tunisia, dating to the late 3rd or early 4th century AD. The horizontal water wheel with angled blades was installed at the bottom of a water-filled, circular shaft. The water from the mill-race entered tangentially the pit, creating a swirling water column which made the fully submerged wheel act like a true turbine.[1]

Ján Andrej Segner developed a reactive water turbine in the mid-18th century. It had a horizontal axis and was a precursor to modern water turbines. It is a very simple machine that is still produced today for use in small hydro sites. Segner worked with Euler on some of the early mathematical theories of turbine design.

In 1820, Jean-Victor Poncelet developed an inward-flow turbine.

In 1826, Benoit Fourneyron developed an outward-flow turbine. This was an efficient machine (~80%) that sent water through a runner with blades curved in one dimension. The stationary outlet also had curved guides.

In 1844, Uriah A. Boyden developed an outward flow turbine that improved on the performance of the Fourneyron turbine. Its runner shape was similar to that of a Francis turbine.

In 1849, James B. Francis improved the inward flow reaction turbine to over 90% efficiency. He also conducted sophisticated tests and developed engineering methods for water turbine design. The Francis turbine, named for him, is the first modern water turbine. It is still the most widely used water turbine in the world today. The Francis turbine is also called a radial flow turbine, since water flows from the outer circumference towards the centre of runner.

Inward flow water turbines have a better mechanical arrangement and all modern reaction water turbines are of this design. As the water swirls inward, it accelerates, and transfers energy to the runner. Water pressure decreases to atmospheric, or in some cases subatmospheric, as the water passes through the turbine blades and loses energy.

Around 1890, the modern fluid bearing was invented, now universally used to support heavy water turbine spindles. As of 2002, fluid bearings appear to have a mean time between failures of more than 1300 years.

Around 1913, Viktor Kaplan created the Kaplan turbine, a propeller-type machine. It was an evolution of the Francis turbine but revolutionized the ability to develop low-head hydro sites.

A new concept

All common water machines until the late 19th century (including water wheels) were basically reaction machines; water pressure head acted on the machine and produced work. A reaction turbine needs to fully contain the water during energy transfer.

In 1866, California millwright Samuel Knight invented a machine that took the impulse system to a new level.[2][3] Inspired by the high pressure jet systems used in hydraulic mining in the gold fields, Knight developed a bucketed wheel which captured the energy of a free jet, which had converted a high head (hundreds of vertical feet in a pipe or penstock) of water to kinetic energy. This is called an impulse or tangential turbine. The water's velocity, roughly twice the velocity of the bucket periphery, does a u-turn in the bucket and drops out of the runner at low velocity.

In 1879, Lester Pelton (1829-1908), experimenting with a Knight Wheel, developed a double bucket design, which exhausted the water to the side, eliminating some energy loss of the Knight wheel which exhausted some water back against the center of the wheel. In about 1895, William Doble improved on Pelton's half-cylindrical bucket form with an elliptical bucket that included a cut in it to allow the jet a cleaner bucket entry. This is the modern form of the Pelton turbine which today achieves up to 92% efficiency. Pelton had been quite an effective promoter of his design and although Doble took over the Pelton company he did not change the name to Doble because it had brand name recognition.

Turgo and Crossflow turbines were later impulse designs.

Theory of operation

Flowing water is directed on to the blades of a turbine runner, creating a force on the blades. Since the runner is spinning, the force acts through a distance (force acting through a distance is the definition of work). In this way, energy is transferred from the water flow to the turbine

Water turbines are divided into two groups; reaction turbines and impulse turbines.

The precise shape of water turbine blades is a function of the supply pressure of water, and the type of impeller selected.

Reaction turbines

Reaction turbines are acted on by water, which changes pressure as it moves through the turbine and gives up its energy. They must be encased to contain the water pressure (or suction), or they must be fully submerged in the water flow.

Newton's third law describes the transfer of energy for reaction turbines.

Most water turbines in use are reaction turbines and are used in low (<30m/98 ft) and medium (30-300m/98–984 ft) head applications. In reaction turbine pressure drop occurs in both fixed and moving blades.

Impulse turbines

Impulse turbines change the velocity of a water jet. The jet pushes on the turbine's curved blades which changes the direction of the flow. The resulting change in momentum (impulse) causes a force on the turbine blades. Since the turbine is spinning, the force acts through a distance (work) and the diverted water flow is left with diminished energy.

Prior to hitting the turbine blades, the water's pressure (potential energy) is converted to kinetic energy by a nozzle and focused on the turbine. No pressure change occurs at the turbine blades, and the turbine doesn't require a housing for operation.

Newton's second law describes the transfer of energy for impulse turbines.

Impulse turbines are most often used in very high (>300m/984 ft) head applications .

Power

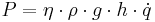

The power available in a stream of water is;

where:

power (J/s or watts)

power (J/s or watts) turbine efficiency

turbine efficiency density of water (kg/m³)

density of water (kg/m³) acceleration of gravity (9.81 m/s²)

acceleration of gravity (9.81 m/s²) head (m). For still water, this is the difference in height between the inlet and outlet surfaces. Moving water has an additional component added to account for the kinetic energy of the flow. The total head equals the pressure head plus velocity head.

head (m). For still water, this is the difference in height between the inlet and outlet surfaces. Moving water has an additional component added to account for the kinetic energy of the flow. The total head equals the pressure head plus velocity head.

= flow rate (m³/s)

= flow rate (m³/s)

Pumped storage

Some water turbines are designed for pumped storage hydroelectricity. They can reverse flow and operate as a pump to fill a high reservoir during off-peak electrical hours, and then revert to a turbine for power generation during peak electrical demand. This type of turbine is usually a Deriaz or Francis in design.

Efficiency

Large modern water turbines operate at mechanical efficiencies greater than 90% (not to be confused with thermodynamic efficiency).

Types of water turbines

Reaction turbines:

Impulse turbine

- Waterwheel

- Pelton

- Turgo

- Crossflow (also known as the Michell-Banki or Ossberger turbine)

- Jonval turbine

- Reverse overshot water-wheel

- Archimedes' screw turbine

Design and application

Turbine selection is based mostly on the available water head, and less so on the available flow rate. In general, impulse turbines are used for high head sites, and reaction turbines are used for low head sites. Kaplan turbines with adjustable blade pitch are well-adapted to wide ranges of flow or head conditions, since their peak efficiency can be achieved over a wide range of flow conditions.

Small turbines (mostly under 10 MW) may have horizontal shafts, and even fairly large bulb-type turbines up to 100 MW or so may be horizontal. Very large Francis and Kaplan machines usually have vertical shafts because this makes best use of the available head, and makes installation of a generator more economical. Pelton wheels may be either vertical or horizontal shaft machines because the size of the machine is so much less than the available head. Some impulse turbines use multiple water jets per runner to increase specific speed and balance shaft thrust.

Typical range of heads

|

• Hydraulic wheel turbine |

0.2 < H < 4 (H = head in m) |

Specific speed

The specific speed  of a turbine characterizes the turbine's shape in a way that is not related to its size. This allows a new turbine design to be scaled from an existing design of known performance. The specific speed is also the main criteria for matching a specific hydro site with the correct turbine type. The specific speed is the speed with which the turbine turns for a particular discharge Q, with unit head and thereby is able to produce unit power.

of a turbine characterizes the turbine's shape in a way that is not related to its size. This allows a new turbine design to be scaled from an existing design of known performance. The specific speed is also the main criteria for matching a specific hydro site with the correct turbine type. The specific speed is the speed with which the turbine turns for a particular discharge Q, with unit head and thereby is able to produce unit power.

Affinity laws

Affinity Laws allow the output of a turbine to be predicted based on model tests. A miniature replica of a proposed design, about one foot (0.3 m) in diameter, can be tested and the laboratory measurements applied to the final application with high confidence. Affinity laws are derived by requiring similitude between the test model and the application.

Flow through the turbine is controlled either by a large valve or by wicket gates arranged around the outside of the turbine runner. Differential head and flow can be plotted for a number of different values of gate opening, producing a hill diagram used to show the efficiency of the turbine at varying conditions.

Runaway speed

The runaway speed of a water turbine is its speed at full flow, and no shaft load. The turbine will be designed to survive the mechanical forces of this speed. The manufacturer will supply the runaway speed rating.

Maintenance

Turbines are designed to run for decades with very little maintenance of the main elements; overhaul intervals are on the order of several years. Maintenance of the runners and parts exposed to water include removal, inspection, and repair of worn parts.

Normal wear and tear includes pitting from cavitation, fatigue cracking, and abrasion from suspended solids in the water. Steel elements are repaired by welding, usually with stainless steel rods. Damaged areas are cut or ground out, then welded back up to their original or an improved profile. Old turbine runners may have a significant amount of stainless steel added this way by the end of their lifetime. Elaborate welding procedures may be used to achieve the highest quality repairs.[4]

Other elements requiring inspection and repair during overhauls include bearings, packing box and shaft sleeves, servomotors, cooling systems for the bearings and generator coils, seal rings, wicket gate linkage elements and all surfaces.[5]

Environmental impact

Water turbines are generally considered a clean power producer, as the turbine causes essentially no change to the water. They use a renewable energy source and are designed to operate for decades. They produce significant amounts of the world's electrical supply.

Historically there have also been negative consequences, mostly associated with the dams normally required for power production. Dams alter the natural ecology of rivers, potentially killing fish, stopping migrations, and disrupting peoples' livelihoods. For example, American Indian tribes in the Pacific Northwest had livelihoods built around salmon fishing, but aggressive dam-building destroyed their way of life. Dams also cause less obvious, but potentially serious consequences, including increased evaporation of water (especially in arid regions), build up of silt behind the dam, and changes to water temperature and flow patterns. Some people believe that it is possible to construct hydropower systems that divert fish and other organisms away from turbine intakes without significant damage or loss of power; historical performance of diversion structures have been poor. In the United States, it is now illegal to block the migration of fish, for example the endangered great white sturgeon in North America, so fish ladders must be provided by dam builders. The actual performance of fish ladders is often poor.

See also

References

- ^ a b Wilson 1995, pp. 507f.; Wikander 2000, p. 377; Donners, Waelkens & Deckers 2002, p. 13

- ^ W. A. Doble, The Tangential Water Wheel, Transactions of the American Institute of Mining Engineers, Vol. XXIX, 1899.

- ^ W. F. Durrand, The Pelton Water Wheel, Stanford University, Mechanical Engineering, 1939.

- ^ Cline, Roger:Mechanical Overhaul Procedures for Hydroelectric Units (Facilities Instructions, Standards, and Techniques, Volume 2-7); United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation, Denver, Colorado, July 1994 (800KB pdf).

- ^ United States Department of the Interior Bureau of Reclamation; Duncan, William (revised April 1989): Turbine Repair (Facilities Instructions, Standards & Techniques, Volume 2-5) (1.5 MB pdf).

Sources

- Donners, K.; Waelkens, M.; Deckers, J. (2002), "Water Mills in the Area of Sagalassos: A Disappearing Ancient Technology", Anatolian Studies 52: 1–17

- Wikander, Örjan (2000), "The Water-Mill", in Wikander, Örjan, Handbook of Ancient Water Technology, Technology and Change in History, 2, Leiden: Brill, pp. 371–400, ISBN 90-04-11123-9

- Wilson, Andrew (1995), "Water-Power in North Africa and the Development of the Horizontal Water-Wheel", Journal of Roman Archaeology 8: 499–510

External links

- Introductory turbine math

- European Union publication, Layman's hydropower handbook,12 MB pdf

- "Selecting Hydraulic Reaction Turbines", US Bureau of Reclamation publication, 48 MB pdf

- "Laboratory for hydraulique machines", Lausanne (Switzerland)

- DoradoVista, Small Hydro Power Information

|

|||||